|

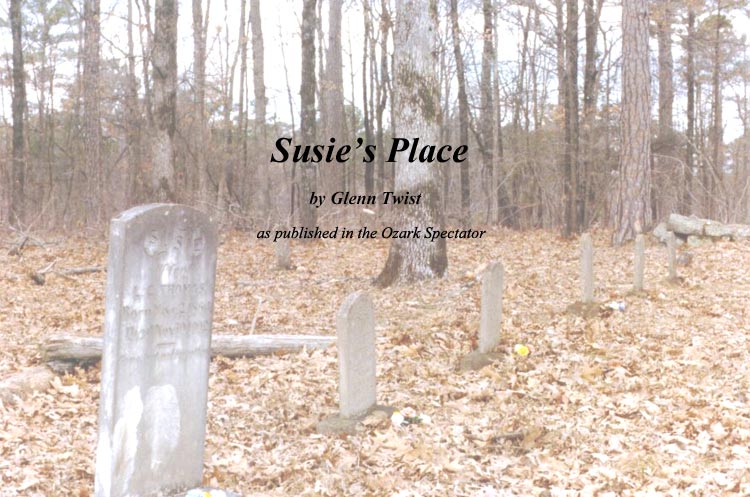

They stand as sentries, straight, erect, shoulder-to-shoulder and six wide, a battle field picket line prepared to repulse the resurging woodlands that threaten them with oblivion. Isolated deep in the forest, and visited mainly by hunters, this unnamed family burying ground is a true-life vignette of the past. Six thin slabs of moss-covered marble dominate the plot. No more incongruous than the images visualized in Rorschach inkblots, the headstones bring to mind the hand scrub-boards that predated our modern home laundry machines. One marker, slightly taller than the others, has the word "Susie" carved gracefully above the name of her husband. The other five stones, all the same in size are spaced a grave's width apart. Making a poignant statement, the words "Infant Child" are carved on each of the smaller stones. Unmindful that anything artificial is out of place on this all-natural mountainside, each gravesite wears a small bouquet of plastic flowers. These tiny spots of enduring color, bright against the dull brown of dry leaves, silently proclaim that someone remembers. An appropriate identification for this nameless plot would be Susie's Place. In fact, any other name ignores the obvious. It was more than a century ago that Susie's kin came to Hawkins Flat, a place high on the side of Black Mountain. Then it was a place more suited to deer, bears, and wild turkeys than people. Today, she and I have a common bond, our love for the mountains. When standing near her place I expect to feel a gentle breeze. I imagine it's the air being puffed by her skirts as she swishes about tidying up the place. It's her way of saying, "Glad to see you again." Susie's burying place, and the graves of her children as well, mutely declare the mountain more brutal than majestic. These headstones serve as a reminder that life on the mountain was often a painful gauntlet that had to be run. Although not entirely barren of happy moments, Susie's life on her hillside home place was little more than a constant encounter with the sadness that, according to her "good book," preceded eternal joy. When I stand near this almost forgotten plot, compassionate admiration well’s up from within me. Tears sometimes flow and when they do, I'm not embarrassed, not even a little bit. My respect for Susie and for all the other people who attempted a homestead on Hawkins Flat is drawn from a bottomless well. Susie's birthplace, her father's homestead on Black Mountain, marked the end of an era in American history; the westernmost point reached by the tidal wave of humans that surged through the Cumberland Gap shortly after the cessation of our nation's Second War of Independence. Because American's heartland, once lying primordial just waiting for settlers, had already been taken, she and her husband lived out their lives on her father's homestead there on Hawkins Flat. The ground Susie had inherited was so worn-out and unproductive it could hardly be called a farm. Still, by girdling virgin trees and toting uncountable rocks to the edge of the field, her family had made a few acres tillable. With hoes and sticks they coaxed subsistence --mainly peas and corn --from their rocky clearing. Oak trees abounded the hillsides. Susie's pigs fattened on the annual feast; acorns dropped on the forested floor. She saw the berry vines proliferating in the blackened scars of forest "burns," the poke-salad growing abundant along fence lines, and the dandelion and plantain, plentiful year-round in the hollows, as nourishment provided by the Lord. During a good winter, her husband's traps yielded furs that were traded for necessities, such as salt, sugar, flour, maybe a small plug or two of sweet store-tobacco, and perhaps a few yards of cloth. For their impoverished hand to mouth existence, she and her children worked "devil-hard" and from "can to can't." Kept from being one room by a lean-to, Susie's wretched dwel1ing, a log pen with a roof, was more hovel than home. As with the other mountain women in her time, she accepted the stupefying monotony, as well as the cruel hopelessness of her daily existence, without protest. It was all she knew. Besides, her faith was built on the rock of fatalism. She regarded her harsh, unyielding circumstances as being God's will. Susie believed in a God that spit fire, threw arrows, and did battle with Satan. She didn't know the tinsel of choir robes and paid preachers. Her Lord came plain. Because she was illiterate, a common state for mountain folks in her time, what she believed had roots as much in superstition as in the Bible. Having nothing in this world, she looked to the next for her promised reward. In her way of thinking, life on earth was only an interlude that linked her birth to her eternal paradise. She endured its merciless tyranny because she saw it as a testing period that, when endured, assured her everlasting life in the hereafter. For mountain families, danger and death lurked behind every tree. In addition to naturally occurring misfortunes, they also had to contend with lawless hoodlums, known to kill the male adults and ravish the females as they looted their victim's meager provisions and livestock. While still a small boy, Susie's husband had been forced to watch a band of "backshooters" murder his father before driving off his family’s s precious animals. Life in the mountains was a cruel reality that weighed heavily on all members of the backwoods family; however, it was the mothers who had to bear the heavier burden. One glimpse at the five infant headstones, rowed alongside her own, vanishes all doubts as to Susie's main role in life. It was motherhood and she filled that role until life passed from her. As expected of all mountain women, she painfully withstood pregnancy with her next child, even while nursing the last. Standing silently, those grave markers also attest to the heart-rending tragedy that stalked motherhood in the mountains during Susie's time. In her short lifetime, Susie did her part to fulfill the biblical admonition, go forth and multiply. Even though she was called from her earthly travail at only thirty-six years of age, she had the time to bear twelve children--seven surviving infancy. Susie's inhospitable home place, no longer able to provide sustenance for a growing number of families, gave up her offspring to the towns that had sprouted near the bottom of her mountain. With their departure, the laughter of young people at play will not again ricochet across Hawkins Flat. However, her departing children left behind a joyful mother who found her immortality in the heavenly home for which she lived. In Susie's way of arranging the universe, happiness reigns over her place here on the mountainside. Susie's Place, now hidden deep in the resurging forest, has gone back to being a part of an unchanging world. To be sure, the trees around her are recycled every quarter-century or so. However, in heaven's millennium, this time span is a bagatelle. Without marking the azure sky high overhead, birds timelessly sweep back and forth. The sound of raincrows, as they make their baleful forecast, noise of woodpeckers drumming lunch from distant snags, or the noise of leaves being rustled by the wind and squirrels are so much a part of things they only punctuate the placidity that has settled over the mountain. Hawkins Flat has evolved into a tiny niche, an isolated spot in the troubled world, where peace reigns supreme. The air surrounding Susie's Place is saturated with tranquility so intense it discourages all but quiet retrospection, suggesting that everything of consequence has already been said and done.

© 1986

Transcribed and contributed by Ernie Matlock Glenn too was laid to rest at Susie’s Place, 'where peace reigns supreme’. - Betty Finger |